Being is one of the main philosophical categories. The study of existence is carried out in such a “branch” philosophical knowledge, as ontology. The life-oriented orientation of philosophy, in essence, puts the problem of being at the center of any philosophical concept. However, attempts to reveal the content of this category face great difficulties: at first glance, it is too broad and vague. On this basis, some thinkers believed that the category of being is an “empty” abstraction. Hegel wrote: “For thought there can be nothing more insignificant in its content than being.” F. Engels, polemicizing with German philosopher E. Dühring, also believed that the category of being can help us little in explaining the unity of the world and the direction of its development. However, in the 20th century, an “ontological turn” is planned; philosophers call for returning the category of being to its true meaning. How is the rehabilitation of the idea of being consistent with close attention to the inner world of a person, his individual characteristics, and the structures of his mental activity?

The content of being as a philosophical category is different from its everyday understanding. Everyday existence is everything that exists: individual things, people, ideas, words. It is important for a philosopher to find out what it means to “be”, to exist? Is the existence of words different from the existence of ideas, and the existence of ideas different from the existence of things? Whose mode of existence is more durable? How to explain the existence of individual things - “from themselves”, or to look for the basis of their existence in something else - in the original principle, the absolute idea? Does such an Absolute Being exist, independent of anyone and nothing, determining the existence of all other things, and can a person know it? And, finally, the most important thing: what are the features of human existence, what are its connections with Absolute Being, what are the possibilities for strengthening and improving one’s existence? The basic desire to “be,” as we have seen, is the main “vital prerequisite” for the existence of philosophy. Philosophy is the search for forms of human involvement in Absolute Being, securing oneself in being. Ultimately, the question of being is a question of overcoming non-existence, of life and death.

The concept of being is closely related to the concept of substance. The concept of substance (from Latin substantia - essence) has two aspects:

- 1. Substance is something that exists “by itself” and does not depend for its existence on anything else.

- 2. Substance is the fundamental principle; the existence of all other things depends on its existence.

From these two definitions it is clear that the content of the concepts of being and substance are in contact. At the same time, the content of the concept of substance is more articulated, the explanatory function of the concept of “substance”, in contrast to “being,” is clear. “In a natural way” the content of one concept is replaced by another: when talking about being, we most often talk about the fundamental principle of the world, about substance. Further specification leads to the fact that philosophers begin to talk about being as something quite definite - a spiritual or material-material origin. Thus, the question of being as a question of the meaning of human existence is replaced by the question of the origin of everything that exists. A person turns into a simple “consequence” of a material or spiritual origin.

Ordinary consciousness perceives the terms “to be”, “to exist”, “to be present” as synonyms. Philosophy uses the terms “to be” and “being” to denote not just existence, but that which guarantees existence. Therefore, the word “being” receives a special meaning in philosophy, which can only be understood by turning to consideration from a historical and philosophical perspective to the problems of being.

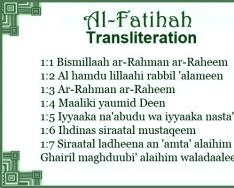

The term “being” was first introduced into philosophy by the ancient Greek philosopher Parmenides to designate and at the same time solve one real problem of his time in the 4th century.

BC people began to lose faith in the traditional gods of Olympus, mythology increasingly began to be viewed as fiction. Thus, the foundations and norms of the world, the main reality of which were gods and traditions, collapsed. The world and the cosmos were no longer strong and reliable: everything became shaky and shapeless, unstable. Man lost his vital support. In the depths of human consciousness, despair and doubt arose, seeing no way out of the impasse. There was a need for a way out to something strong and reliable.

People needed faith in a new force.

Philosophy, represented by Parmenides, realized the current situation, which turned into a tragedy for human existence, i.e. existence. To designate the existential-life situation and ways to overcome it, Parmenides introduced the concept and problematics of being into philosophy. Thus, the problematic of being was philosophy’s response to the needs and demands of the ancient era.

How does Parmenides characterize being? Being is what exists behind the world of sensory things, and this is thought. By asserting that being is thought, he meant

Not the subjective thought of man, but the Logos - the cosmic Mind. Being is one and unchangeable, absolutely, has no division within itself into subject and object, it is all possible completeness of perfection. Defining being as a true being, Parmenides taught that it did not arise, is not destroyed, unique, motionless, endless in time.

The Greek understanding of being as an essential, unchanging, immovable being determined trends for many centuries spiritual development Europe. This focus on searching for the ultimate foundations of the existence of the world and man was characteristic feature both ancient and medieval philosophy.

Outstanding philosopher of the twentieth century. M. Heidegger, who devoted 40 years of his life to the problem of being, argued that the question of being and its solution by Parmenides sealed the fate of the Western world.

The theme of being has been central to metaphysics since antiquity. For Thomas Aquinas God and only he alone is being as such, authentic. Everything else created by him has an inauthentic existence.

Philosophers of the New Age mainly associate the problem of being only with man, denying objectivity to being. Thus, Descartes argued that the act of thinking - I think - is the simplest and most self-evident basis for the existence of man and the world. He made thought into being, and declared man to be the creator of thought. This meant that being had become subjective. Heidegger expressed it this way: “The being of beings has become subjectivity.” Subsequently, Kant wrote about being dependent on knowledge. Representatives of empirio-criticism saw the only basis of existence in human sensations, and existentialists directly stated that man and he alone is the true and ultimate being.

Philosophers who in modern times considered the problem of being from an objective position were divided into two camps - idealists and materialists. Representatives of idealistic philosophy were characterized by the extension of the concept of being not only and even not so much to matter as to consciousness, the spiritual. For example, N. Hartmann in the twentieth century. understood existence as spiritual existence.

French materialists considered nature as a real being. For Marx, being includes nature and society.

The specific attitude of Russian philosophy to the problem of being has its origins in Orthodox religion. It is existence in God that is the essence of Russian religiosity, which determines the philosophical solution to the problem of existence. The spiritual creativity of Russian thinkers (both secular and religious) was aimed at understanding the deepest ontological, existential sources human life.

If in modern times the transformation of the ancient idea of the objectivity of existence began, its transformation into subjective, then in the twentieth century. this process deepened. Now even God began to depend on man’s a priori internal attitude to search for the unconditional. Refusal of any kind of substantiality became the norm of philosophizing in the twentieth century.

XX century marked by a crusade against reason. By speaking out against reason, thinkers expressed the growing awareness in society of the meaninglessness and unsupportability of existence. Having abandoned God (“God is dead” - Nietzsche), no longer relying on reason, man of the 20th century. I was left alone with my body. The cult of the body began, which is a sign of paganism, or rather neo-paganism.

Changing worldview in the twentieth century. entailed not only new production question of being, but also a revision of style and norms intellectual activity. Thus, postmodern philosophy demanded the Heraclitean version of being as becoming, which influenced the existing forms of philosophizing. Being began to be seen as becoming. Postmodern philosophy, based on the idea of being as becoming, has taken upon itself the task of showing and objectifying thought in the process of becoming. A new attitude to existence is associated with deep ideological shifts occurring in the consciousness of modern people.

The philosophical doctrine of being is ontology (from the Greek “ontos” - existing and “logos” - doctrine). Existence can be defined as the universal, universal and unique ability to exist that every reality possesses. Being is opposed to non-being, which indicates the absence of anything. The concept of “being” is the central initial category in philosophical understanding the world, through which all other concepts are determined - matter, movement, space, time, consciousness, etc. The beginning of cognition is the fixation of a certain being, then there is a deepening into being, the discovery of its independence.

The world appears to a person as an integral formation, including many things, processes, phenomena and states of human individuals. We call all this universal being, which is divided into natural being and social being. Natural existence refers to those states of nature that existed before man and exist outside of his activity. A characteristic feature of this being is objectivity and its primacy in relation to other forms of being. Social existence- this is being produced by a person in the course of his purposeful activity. Derived from material-substrate being is ideal being, the world of the mental and spiritual.

Along with the named types of being, the following basic forms of being are distinguished: actual objective being, potential being and value being. If, when defining the first two forms of being, they mean that certain objects, processes, phenomena, properties and relationships either exist in reality itself, or are in “possibility”, i.e. may arise, such as a plant from a seed, then in relation to values and value relations their existence is simply recorded.

Forms of being are also distinguished by the attributes of matter, noting that there are spatial being and temporary being, and by the forms of movement of matter - physical being, chemical being, biological being, social being.

Other approaches to identifying forms of being are also possible, in particular, one that is based on the fact that the universal connections of being are manifested only through connections

between individual beings. On this basis, it is advisable to highlight the following differing, but also interconnected basic forms of being:

- 1. the existence of things, processes, which in turn is divided into: the existence of things, processes, states of nature, the existence of nature as a whole and the existence of things and processes produced by man;

- 2. human existence, which is divided into human existence in the world of things and specifically human existence;

- 3. the existence of the spiritual (ideal), which is divided into individualized spiritual and objectified (non-individual) spiritual;

- 4. social existence, which is divided into individual existence (the existence of an individual in modern society and the process of its history) and the existence of society.

Representatives of various philosophical directions allocated different types and forms of being and gave them their own interpretation. Idealists created a model of existence in which the role of the existential principle was assigned to the spiritual. It is from this, in their opinion, that design, systemic order, expediency and development in nature should proceed.

Lecture 10. The problem of being in philosophy

The concept of “being” was introduced into philosophy by Parmenides back in the 6th century. BC and since then it has become one of the most important categories philosophy, expressing the problem of the existence of reality in its most general form.

The initial prerequisite for human life is the recognition that the world exists. But, having recognized the existence of the world, we involuntarily raise the question of its past and future. And here different answers are possible. Some philosophers argued that the world has always been, is and always will be. Others, agreeing with this position, believed that the world has a beginning and an end in time and space. In other words, the idea of the existence of the world as a whole was combined in philosophy with the thesis of either the transitory or enduring existence of the world.

The problem of being includes several interrelated aspects. The first aspect consists in the unity of the enduring existence of nature as a whole and the transitory existence of individual things and processes of nature, having a beginning and an end in time and space

The second aspect shows that the world in the process of existence forms an inextricable unity, a universal integrity, i.e. the principle of existence is equally possessed by nature, society, man, thoughts, ideas.

The third aspect is related to the fact that the world as a whole and everything that exists in it is a reality that has an internal logic of its existence and actually precedes the consciousness and actions of people.

In philosophy, two meanings of being have developed. In the narrow sense of the word, it is an objective world that exists independently of human consciousness. Being in this meaning is identified with the concept of “matter”. IN in a broad sense the words being are everything that exists: matter, consciousness, feelings and fantasies of people.

There are four main forms of existence: the existence of things, the existence of man, the existence of the spiritual, the existence of the social.

The existence of things. Historically, the first prerequisite for the existence of people has been and remains the things and processes of nature that exist outside and independently of human consciousness and activity. Nature is the environment in which man has been formed over thousands of years. The formation of man took place in the process of increasingly complex labor activity, during which a whole world of things was created, called by K. Marx “second nature”. In the form of its existence, the “second nature” is in many ways similar to the first, from which it is born, and in essence it has the most important distinctive features. First of all, their existence is associated with the process of objectification and deobjectification.

Objectification is a process during which the knowledge, skills, abilities, and social experience of the person creating it are transferred to the object’s nature. As a result, the object of nature is transformed in accordance with the current needs of people and the method of satisfying them.

Disobjectification is the process of transferring to a person the social qualities inherent in the product of labor, thanks to which the object satisfies a specific need.

Objects of “second nature” embody human labor and knowledge. To master a subject, each person must have an idea of their purpose, operating principle, design features, etc. The main difference between the existence of things created by man and the existence of natural things is that their existence is a socio-historical existence, carried out in the process of objective and practical activity of people.

Human existence. It is divided into human existence in the world of things and specific human existence. The doctrine of human existence answers first of all the question of how exactly a person exists. The primary prerequisite for human existence is the existence of his body as an object of nature, subject to the laws of biological evolution and in need of satisfying necessary needs. A person must first of all have food, clothing, shelter, because without this human existence is generally impossible.

The existence of an individual person is a dialectical unity of body and spirit. On the one hand, the functioning of the human body is closely related to the activity of the brain and nervous system, on the other hand, a healthy body creates a good basis for improving thinking, developing spiritual activity and satisfying spiritual needs. At the same time, it is also well known how great the role of the human spirit is in maintaining a person’s physical strength.

It is important to note that the existence of man as a thinking and feeling thing was one of the prerequisites that prompted man to engage in productive activity and communication. Nature did not provide people with everything necessary for a normal existence and they were forced to unite to produce the items necessary to satisfy constantly emerging needs.

In reality, there is a concrete, individual person who can be considered as a thinking and feeling thing, like a natural body. And at the same time, a person exists as an individual, as a representative of the human race, located at a given stage of its development. At the same time, man also exists as a socio-historical being, as a subject and an object. human history. Human existence is objective in relation to the consciousness of individual people and even entire generations. However, the existence of people is by no means absolutely independent of consciousness. It is the unity of the natural and spiritual, individual and generic, personal and social. Human existence, according to Marx, is the real process of people’s lives, their activity to satisfy their needs. The primacy among all types of activity belongs to labor activity, labor.

Being spiritual. Spirituality includes processes of consciousness and the unconscious, norms and principles human communication, knowledge materialized in the forms of natural and artificial languages. There is a distinction between individualized spirituality, the existence of which is inseparable from the specific life activity of the individual, and objectified spirituality, which can exist separately from the individual and his activity.

The individualized existence of the spiritual includes consciousness, self-consciousness and the unconscious. The individualized spiritual is not divorced from the evolution of being as a whole; it does not exist separately from the life activity of the individual. Individualized spirituality in its essence is a special type of spirituality, also conditioned by the existence of society and the development of history.

The specificity of the objectified spiritual lies in the fact that its elements (ideas, ideals, norms, values, languages, etc.) are able to be preserved, improved and freely move in social space and time.

Being social. The existence of the social is divided into the existence of an individual person in society and the process of history and the existence of society as a social phenomenon.

Each individual person does not live in isolation, but is at the same time a member of some specific social education, enters into diverse connections and relationships with other individuals. In the course of his life, he constantly influences the people around him and, in turn, is influenced by other individuals, social groups and institutions. Man, on the one hand, is an object historical process, constantly getting involved in diverse historical events, and on the other hand, he increasingly becomes a subject of historical action, consciously intervening in historical events in order to influence the course of history in accordance with his needs and interests.

The existence of society includes socio-economic and political processes occurring in society, social, economic, political relations of individuals, groups, classes. The existence of society finds its expression in interstate and civil wars, socio-economic and political reforms, in transitions from one stage of social organization to another.

Topic No. 14: Ontology: basic concepts and principles.

No. 1 The concept of being, its aspects and basic forms

The category of being is of great importance both in philosophy and in life. The content of the problem of being includes reflections on the world and its existence. The term “Universe” refers to the entire vast world, from elementary particles to metagalaxies. In philosophical language, the word “Universe” can mean existence or the universe.

Throughout the entire historical and philosophical process, in all philosophical schools, directions, the question of the structure of the universe was considered. The initial concept on the basis of which the philosophical picture of the world is built is the category of being. Being is the broadest, and therefore the most abstract, concept.

Since antiquity, there have been attempts to limit the scope of this concept. Some philosophers naturalized concept of being. For example, the concept of Parmenides, according to which being is a “sphere of spheres,” something motionless, self-identical, which contains all of nature. Or in Heraclitus - as something constantly becoming. The opposite position tried to idealize the concept of being, for example, in Plato. For existentialists, being is limited to the individual existence of a person. The philosophical concept of being does not tolerate any limitation. Let us consider what meaning philosophy puts into the concept of being.

First of all, the term “to be” means to be present, to exist. Recognition of the fact of the existence of diverse things in the surrounding world, nature and society, and man himself is the first prerequisite for the formation of a picture of the universe. From this follows the second aspect of the problem of being, which has a significant impact on the formation of a person’s worldview. Being exists, that is, something exists as a reality and a person must constantly reckon with this reality.

The third aspect of the problem of being is associated with the recognition of the unity of the universe. A man in his everyday life, practical activity comes to the conclusion about his community with other people, the existence of nature. But at the same time, the differences that exist between people and things, between nature and society are no less obvious to him. And naturally, the question arises about the possibility of a universal (that is, common) to all phenomena of the surrounding world. The answer to this question is also naturally connected with the recognition of being. All the diversity of natural and spiritual phenomena is united by the fact that they exist, despite the difference in the forms of their existence. And it is precisely thanks to the fact of their existence that they form the integral unity of the world.

Based on the category of being in philosophy, the most general characteristics universe: everything that exists is the world to which we belong. Thus the world has existence. He is. The existence of the world is a prerequisite for its unity. For there must first be peace before one can speak of its unity. It acts as the total reality and unity of nature and man, material existence and the human spirit.

There are 4 main forms of existence:

1. the first form is the existence of things, processes and natural phenomena.

2. the second form is human existence

3. the third form is the existence of the spiritual (ideal)

4. fourth form – being social

First form. The existence of things, processes and natural phenomena, which in turn are divided into:

» the existence of objects of primary nature;

» the existence of things and processes created by man himself.

The essence is this: the existence of objects, objects of nature itself, is primary. They exist objectively, that is, independently of man - this is the fundamental difference between nature as a special form of being. The formation of a person determines the formation of objects of a secondary nature. Moreover, these objects enrich objects of primary nature. And they differ from objects of primary nature in that they have a special purpose. The difference between the existence of “secondary nature” and the existence of natural things is not only the difference between the artificial (man-made) and the natural. The main difference is that the existence of “second nature” is a socio-historical, civilized existence. Between the first and second nature, not only unity and interconnection are found, but also differences.

Second form. Human existence, which is divided into:

» human existence in the world of things (“a thing among things”);

» specific human existence.

The essence: a person is “a thing among things.” Man is a thing because he is finite, like other things and bodies of nature. The difference between a person as a thing and other things is in his sensitivity and rationality. On this basis, specific human existence is formed.

The specificity of human existence is characterized by the interaction of three existential dimensions:

1) man as a thinking and feeling thing;

2) man as the pinnacle of the development of nature, a representative of the biological type;

3) man as a socio-historical being.

Third form. The existence of the spiritual (ideal), which is divided into:

» individualized spiritual being;

» objectified (non-individual) spiritual.

Individualized spiritual being is the result of the activity of consciousness and, in general, the spiritual activity of a particular person. It exists and is based on the internal experience of people. Objectified spiritual being - it is formed and exists outside of individuals, in the bosom of culture. The specificity of individualized forms of spiritual existence lies in the fact that they arise and disappear with an individual person. Those of them that are transformed into a second non-individualized spiritual form are preserved.

So being is general concept, the most general thing, which is formed by abstracting from the differences between nature and spirit, the individual and society. We are looking for commonality between all phenomena and processes of reality. And this generality is contained in the category of being - a category reflecting the fact of the objective existence of the world.

No. 2 The concept of matter, the evolutionary content of the concept of matter in the process of historical development.

The unifying basis of being is called substance. Substance (from Latin “essence”) means the fundamental principle of everything that exists (the internal unity of the diversity of specific things, phenomena and processes by which and through which they exist). Substance can be ideal and material. As a rule, philosophers strive to create a picture of the universe based on one principle (water, fire, atoms, matter, ideas, spirit, etc.). The doctrine that accepts one principle, one substance as the basis of everything that exists is called monism (from the Latin “mono” - one). Monism is opposed by dualism, which recognizes two equivalent principles (2 substances) as a basis. The monistic approach predominates in the history of philosophy. The most pronounced dualistic tendency is revealed only in philosophical systems Descartes and Kant.

In accordance with the solution to the main ideological issue in the history of philosophy, there were two main forms of monism: idealistic and materialistic monism.

Idealistic monism originates from Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle. Numbers, ideas, forms and other ideal principles act as the foundations of the universe. Idealist monism receives its highest development in Hegel's system. In Hegel, the fundamental principle of the world in the form of an abstract idea is elevated to the level of substance.

The materialist concept of the universe received its most comprehensive development in Marxist-Leninist philosophy. Marxist-Leninist philosophy continues the tradition of materialist monism. This means that it recognizes matter as the basis of existence.

The concept of “matter” has gone through several stages in its historical development. The first stage is the stage of its visual and sensory representation in ancient Greek philosophical teachings (Thales, Anaximenes, Heraclitus and others). The world was based on certain natural elements: water, air, fire, etc. Everything that existed was considered a modification of these elements.

The second stage is the stage of material-subtractive representation. Matter was identified with matter, with atoms, with complexes of their properties, including the property of indivisibility (Bacon, Locke). This physicalist understanding of matter reached its greatest development in the works of philosophical materialists of the 18th century. La Mettrie, Helvetia, Holbach. In fact, the materialistic philosophy of the 17th – 18th centuries transformed the concept of “being” into the concept of “matter”. In conditions when science has shaken faith in God as the absolute and guarantor of existence, human concern about the foundations of the existence of the world was removed in the category of “matter.” With its help it was substantiated as true existing being the natural world, which was declared self-sufficient, eternal, uncreated, and not in need of justification. As a substance, matter had the properties of extension, impenetrability, heaviness, and mass; as a substance - by the attributes of movement, space, time, and, finally, the ability to cause sensations (Holbach).

The third stage is a philosophical and epistemological idea of matter. It was formed during the crisis of natural science at the beginning of the 20th century. X-ray radiation disproved ideas about the impenetrability of matter; the electrical radiation of uranium, the radioactive decay of atoms - destroyed the idea of \u200b\u200bthe indivisibility of the atom, as the fundamental basis of the concept of “field” described a new state of matter, different from matter.

Matter began to be interpreted as any objective reality, given to a person in his sensations, which are copied, photographed, displayed by our sensations, existing independently of them. In this definition, the sign of existence is given exclusively to the concrete sensory substances themselves. And this position is the position of science. Science and materialism have the same understanding of existence: it is identified with the existence of sensory things, and the function of justifying their existence is attributed to matter. This is the methodological significance of the definition. The formulation of the definition of matter that we have named is called epistemological, since it contains an element of connection between objective reality and consciousness and indicates the derivativeness of consciousness. At the same time, such an understanding of matter cannot become outdated, since it is not strictly connected with the specific structure of matter, but is also unable to cover the entire diversity of the concept of “matter.” Such diversity reveals consideration of matter in a substantial aspect. From this point of view, matter exists only in the variety of concrete objects, through them, and not along with them.

No. 3 Movement, space and time as the main forms of existence of matter.

The inherent properties of a substance in philosophy are called attributes. Dialectical materialism considers motion, space and time as attributes of matter.

Dialectical materialism considers movement as a way of existence of matter. There is no and cannot be movement in the world without matter, just as there is no matter without movement. Movement as an absolute way of existence of matter exists in infinitely diverse types and forms, which are the object of study of concrete, natural and human sciences. The philosophical concept of movement denotes any interaction, as well as changes in the states of objects caused by this interaction. Movement is change in general.

It is characterized by the fact that:

n inseparable from matter, since it is an attribute (an integral essential property of an object, without which the object cannot exist) of matter. You cannot think of matter without movement, just as you cannot think of movement without matter;

n movement is objective, changes in matter can only be made by practice;

n movement is a contradictory unity of stability and variability, discontinuity and continuity;

n movement never gives way to absolute peace. Rest is also a movement, but one in which the qualitative specificity of the object (a special state of movement) is not violated.

The types of movement observed in the objective world can be divided into quantitative and qualitative changes. Quantitative changes are associated with the transfer of matter and energy in space. Qualitative changes are always associated with a qualitative restructuring of the internal structure of objects and their transformation into new objects with new properties. Essentially, we are talking about development. Development is a movement associated with the transformation of the quality of objects, processes or levels and forms of matter.

Considering movement as a way of existence of matter, dialectical materialism asserts that the source of movement should be sought not outside of matter, but in it itself. The world, the Universe, with this approach appears as a self-changing, self-developing integrity.

Other, no less important attributes of matter are space and time. If the movement of matter acts as a method, then space and time are considered as forms of existence of matter. Recognizing the objectivity of matter, dialectical materialism recognizes objective reality space and time. There is nothing in the world except moving matter, which cannot move except in space and time.

The question of the essence of space and time has been discussed since ancient times. In all disputes the question was in what relation space and time relate to matter. There have been two points of view on this issue in the history of philosophy. :

1) the first we call the substantial concept; space and time were interpreted as independent entities, existing along with matter and independently of it (Democritus, Epicurus, Newton). That is, a conclusion is drawn about the independence of the properties of space and time from the nature of the ongoing material processes. Space here is an empty container of things and events, and time is pure duration, it is the same throughout the universe and this flow does not depend on anything.

2) the second concept is called relational (“relatuo” - relationship). Its supporters (Aristotle, Leibniz, Hegel) understood space and time not as independent entities, but as a system of relations formed by moving matter.

Nowadays, the relational concept has a natural scientific basis in the form of the theory of relativity created by A. Einstein. The theory of relativity states that space and time depend on moving matter; in nature there is a single space - time (space-time continuum). In turn, the general theory of relativity states: space and time do not exist without matter, their metric properties (curvature and speed of time) are created by the distribution and interaction of gravitating masses. Thus:

Space– this is the form of existence of matter, characterizing its extent (length, width, height), the structure of coexistence and interaction of elements in all material systems. The concept of space makes sense insofar as matter itself is differentiated and structured. If the world did not have a complex structure, if it were not divided into objects, and those, in turn, into interconnected elements, then the concept of space would not make sense.

To clarify the definition of space, let us consider the question: what properties of the objects captured on it does photography allow us to judge? The answer is obvious: it reflects the structure, and therefore the extent (relative sizes) of these objects, their location relative to each other. Photography, therefore, records the spatial properties of objects, and objects (in this case this is important) coexisting at some point in time.

But the material world does not simply consist of structurally divided objects. These objects are in motion, they represent processes, in them certain qualitative states can be distinguished, replacing one another. Comparing qualitatively different measurements with each other gives us an idea of time.

Time is a form of existence of matter, expressing the duration of existence of material systems, the sequence of changes in states and changes in these systems in the process of development.

To clarify the definition of time, consider the question: why do we have the opportunity, looking at a movie screen, to judge the time characteristics captured on the film of events? The answer is obvious: because the frames replace each other on the same screen, coexisting at this point in space. If we place each frame on its own screen, then we will simply get a collection of photographs...

The concepts of space and time are correlated not only with matter, but also with each other: the concept of space reflects the structural coordination of various objects at the same moment in time, and the concept of time reflects the coordination of the duration of successive objects and their states in the same volume. same place in space.

Space and time are not independent entities, but fundamental forms of being, moving matter, therefore space-time relations are conditioned by matter, depend on it and are determined by it.

Thus, on the basis of a substantial interpretation of matter, dialectical materialism considers the entire diversity of being in all its manifestations from the angle of its material unity. Being, the Universe appears in this concept as an endlessly developing diversity of a single, material world. Developing a specific idea of the material unity of the world is not the function of philosophy. This falls within the competence of the natural and human sciences and is carried out as part of the creation scientific picture peace.

Dialectical materialism, both during its formation and at present, is based on a certain scientific picture of the world. The natural scientific prerequisites for the formation of dialectical materialism were three important discoveries:

1) the law of conservation of energy, which asserts the indestructibility of energy, its transition from one type to another;

2) establishing the cellular structure of living bodies - the cell is the elementary basis of all living things;

3) Darwin's theory of evolution, who substantiated the idea of the natural origin and evolution of life on Earth.

These discoveries contributed to the establishment of the idea of the material unity of the world as a self-developing system.

Having summarized the achievements of the natural sciences, Engels created his own classification of the forms of motion of matter. He identifies 5 forms of movement of matter: mechanical, physical, chemical, biological and social.

The classification of these forms is carried out according to 3 main principles:

1. Each form of movement is associated with a specific material carrier: mechanistic – movement of bodies; physical - atoms; chemical - molecules; biological – proteins; social – individuals, social communities.

2. All forms of matter motion are related to each other, but differ in degree of complexity. More complex forms arise on the basis of less complex ones, but are not their simple sum, but have their own special properties.

3. Under certain conditions, the forms of motion of matter transform into each other.

Further development of natural science forced changes to be made in the classification of forms of motion of matter.

The category of being is of great importance both in philosophy and in life. The content of the problem of being includes reflections on the world and its existence. The term “Universe” refers to the entire vast world, from elementary particles to metagalaxies. In philosophical language, the word “Universe” can mean existence or the universe.

Throughout the entire historical and philosophical process, in all philosophical schools and directions, the question of the structure of the universe was considered. The initial concept on the basis of which the philosophical picture of the world is built is the category of being. Being is the broadest, and therefore the most abstract, concept.

Since antiquity, there have been attempts to limit the scope of this concept. Some philosophers naturalized the concept of being. For example, the concept of Parmenides, according to which being is a “sphere of spheres,” something motionless, self-identical, which contains all of nature. Or in Heraclitus - as something constantly becoming. The opposite position tried to idealize the concept of being, for example, in Plato. For existentialists, being is limited to the individual existence of a person. The philosophical concept of being does not tolerate any limitation. Let us consider what meaning philosophy puts into the concept of being.

First of all, the term “to be” means to be present, to exist. Recognition of the fact of the existence of diverse things in the surrounding world, nature and society, and man himself is the first prerequisite for the formation of a picture of the universe. From this follows the second aspect of the problem of being, which has a significant impact on the formation of a person’s worldview. Being exists, that is, something exists as a reality and a person must constantly reckon with this reality.

The third aspect of the problem of being is associated with the recognition of the unity of the universe. A person in his daily life and practical activities comes to the conclusion about his community with other people and the existence of nature. But at the same time, the differences that exist between people and things, between nature and society are no less obvious to him. And naturally, the question arises about the possibility of a universal (that is, common) to all phenomena of the surrounding world. The answer to this question is also naturally connected with the recognition of being. All the diversity of natural and spiritual phenomena is united by the fact that they exist, despite the difference in the forms of their existence. And it is precisely thanks to the fact of their existence that they form the integral unity of the world.

Based on the category of being in philosophy, the most general characteristic of the universe is given: everything that exists is the world to which we belong. Thus the world has existence. He is. The existence of the world is a prerequisite for its unity. For there must first be peace before one can speak of its unity. It acts as the total reality and unity of nature and man, material existence and the human spirit.

There are 4 main forms of existence:

1. the first form is the existence of things, processes and natural phenomena.

2. second form - human existence

3. third form – the existence of the spiritual (ideal)

4. fourth form – being social

First form. The existence of things, processes and natural phenomena, which in turn are divided into:

» the existence of objects of primary nature;

» the existence of things and processes created by man himself.

The essence is this: the existence of objects, objects of nature itself, is primary. They exist objectively, that is, independently of man - this is the fundamental difference between nature as a special form of being. The formation of a person determines the formation of objects of a secondary nature. Moreover, these objects enrich objects of primary nature. And they differ from objects of primary nature in that they have a special purpose. The difference between the existence of “secondary nature” and the existence of natural things is not only the difference between the artificial (man-made) and the natural. The main difference is that the existence of “second nature” is a socio-historical, civilized existence. Between the first and second nature, not only unity and interconnection are revealed, but also differences.

Second form. Human existence, which is divided into:

» human existence in the world of things (“a thing among things”);

"specific human existence.

The essence: a person is “a thing among things.” Man is a thing because he is finite, like other things and bodies of nature. The difference between a person as a thing and other things is in his sensitivity and rationality. On this basis, specific human existence is formed.

The specificity of human existence is characterized by the interaction of three existential dimensions:

1) man as a thinking and feeling thing;

2) man as the pinnacle of the development of nature, a representative of the biological type;

3) man as a socio-historical being.

Third form. The existence of the spiritual (ideal), which is divided into:

» individualized spiritual being;

» objectified (non-individual) spiritual.

Individualized spiritual being is the result of the activity of consciousness and, in general, the spiritual activity of a particular person. It exists and is based on the internal experience of people. Objectified spiritual being - it is formed and exists outside of individuals, in the bosom of culture. The specificity of individualized forms of spiritual existence lies in the fact that they arise and disappear with an individual person. Those of them that are transformed into a second non-individualized spiritual form are preserved.

So, being is a general concept, the most general, which is formed by abstracting from the differences between nature and spirit, the individual and society. We are looking for commonality between all phenomena and processes of reality. And this generality is contained in the category of being - a category reflecting the fact of the objective existence of the world.

54. Philosophical concept of matter

Understanding who created the world, what underlies the world has always worried people. Answering these questions, philosophers formed two main philosophical directions:

“materialism” - those who believe that the world exists due to the evolution of nature, and “idealism”, which believe that ideas originally existed, and the world is the embodiment of these ideas.

And today one of the pressing problems is the “concept of matter” because it is one of the guiding methodological principles of course scientific research.

The concept of matter in ancient times

The concept of matter is one of the fundamental concepts of philosophy and natural science. Like other scientific concepts, it has its own history.

Every historical era the content of the concept of matter was determined by the level of development of scientific knowledge about the world.

It should be pointed out that the initial ideas about matter arose already in ancient times. Based on everyday experience and observations, ancient materialists suggested that all phenomena around our world have some kind of fundamental principle, an unchanging and indestructible material substance. The substances are: water, air, fire and aineron (undefined substance).

The ancient Greeks spoke about the unlimited divisibility of matter. Thus, according to Anaxagoras, the world is a collection of an infinite number of particles - homeomeries, each of which, in turn, consists of an inexhaustible number of even smaller homeomeries, etc. without end. It was believed that any of these particles contains all the properties material world.

Heraclitus of Ephesus considered fire to be the fundamental principle of all things. By the way, fire in Heraclitus is also an image of perpetual motion. “This cosmos,” he argued, “is the same for everyone, was not created by any of the gods and none of the people, but it always was, is and will be an eternally living fire, gradually flaring up and gradually dying out.”

It must be emphasized that in ancient Greek philosophy a religious-idealistic understanding of matter also developed. Thus, the objective idealist Plato divided reality into the world of ideas and the world of sensory things. The true substance, the root cause of the world, in his opinion, is the “world of ideas”, i.e. world mind god. Matter is an inert, passive mass that is generated and set in motion by a higher spiritual principle, which constitutes its essence.

Note that in the XII-XIII centuries. A new understanding of matter is emerging, from the passive ideas of the ancients. During this period, mathematical, natural and natural sciences split off from philosophy and developed as independent branches. social science. Atomistic ideas predominate in views on matter. Matter is identified with substance consisting of indivisible atoms. Matter is attributed such properties as extension, impenetrability, and inertia. Weight is constant mechanical mass.

The metaphysical understanding of matter was criticized by the founders of dialectical materialism. The inadmissibility of identifying matter with matter and the futility of searching for the fundamental principle of all specific objects was pointed out in particular by F. Engils in his work “Dialectics of Nature”. He believed that atoms are not the simplest, smallest particles of matter; they have a complex structure. Matter, Engils emphasized, “is something other than the totality of matter from which this concept is abstracted, and words such as matter and motion are nothing more than abbreviations in which we cover, in a unique way, their general properties, many different sensory perceived things.”

Definition of matter V.I. Lenin

In the work “Materialism and Empirio-Criticism” V.I. Lenin gave a scientific definition of matter, which is the result of a generalization of the main achievements of natural science of that period: “matter is a philosophical category to designate objective reality, which is copied, photographed, displayed by our sensations, existing independently of them” V.I. Lenin, first of all, emphasizes the objectivity of the existence of matter, its independence from human sensations and consciousness in general.

It is quite obvious that Lenin’s understanding of the essence of matter is fundamentally different from the metaphysical one.

Matter is not reducible V.I. Lenin only refers to material phenomena and processes that are perceived by human senses directly or with the help of instruments; it embraces all objective reality without any restrictions, i.e. not only already known phenomena reality, but also those that can be discovered and studied in the future.

Matter, therefore, is everything that exists outside the consciousness of man, independent of him, as an objective reality. Not only material objects and physical fields are material, but also production relations in society, since they arise and develop in the process of material production, regardless of people’s consciousness.

The thesis that matter disappeared in connection with new discoveries in physics was rightfully challenged by V.I. Lenin, who defended philosophical materialism. Characterizing the true meaning of the expression “matter has disappeared,” V.I. Lenin shows that it is not matter that disappears, but the limit to which we knew matter, that the disappearance of matter, which some scientists and philosophers talk about, has no relation to the philosophical concept about matter, because the philosophical concept (term) matter cannot be confused with natural scientific ideas about the material world. With the development of natural science, one scientific idea of the world (matter) is replaced by another, deeper and more thorough. However, such a change in specific scientific ideas cannot refute the meaning and significance of the philosophical concept (category) “matter,” which serves to designate the objective reality given to a person in his sensations and existing independently of them.

V.I. Lenin also reveals the reasons for the widespread spread of “physical” idealism among natural scientists. Many physicists, he notes, were confused because they did not master dialectics and confused physical ideas about the structure and properties of matter, which change as we penetrate into the depths of matter, with philosophical concept matter, reflecting the unchangeable property of matter to be an objective reality, to exist outside of our consciousness. In this regard, V.I. Lenin considers it necessary to distinguish between the philosophical understanding of matter and physical ideas about its properties and structure, emphasizing that physical ideas do not concern the entire objective reality, but only its individual aspects.

Lenin's definition of matter played an important role in the criticism of "physical" idealism and metaphysics. Being the basis scientific worldview, it reveals the real nature of the material world, equips us with scientific ideas about it, is the foundation for generalizing scientific data, shows the inconsistency of modern idealism, metaphysics, agnosticism, and serves as a weapon in the fight against them. This is the ideological significance of Lenin’s definition of matter.

Considering matter as philosophical category, denoting objective reality, V.I. Lenin thereby continues the materialist line in philosophy. In his definition there is no subsuming of the category “matter” under a broader concept, because such a concept simply does not exist. In this sense of the Withdrawal, “matter” and “objective reality” are synonyms. Matter is contrasted with consciousness, while objectivity is emphasized, as the independence of its existence from consciousness. It is this property: to exist before, outside and independently of consciousness that determines the meaning of the purpose of the philosophical-materialistic idea of matter. The philosophical interpretation of matter has the attribute of universality and denotes all objective reality. With this understanding of matter, there is and cannot be any reference to the physical properties of matter, knowledge of which is relative.

In light of the above, it is quite obvious that the role of defining the concept of matter, understanding the latter as inexhaustible for constructing a scientific picture of the world, solving the problem of reality and knowability of objects and phenomena of the micro and megaworld is very important.

Matter is eternal, uncreated and indestructible. It has always and everywhere existed, and will always and everywhere exist.

Aspects of the existence of science are understood as the essential features of science, which are necessary and sufficient to define such a phenomenon as science and distinguish it from other phenomena of human life.

Aspects of the existence of science are the following.

1. Science is a special kind cognitive activity, the purpose of which is to achieve objective information about the world around us, which allows for the effective use of scientific knowledge in practical activities. This aspect of the existence of science was one of the first to be recognized in philosophy. Yes, back in ancient philosophy identified science as a special type of knowledge, since it is scientific knowledge that brings one closer to true existence and carries the truth. In the philosophy of science of the 20th century, the study of this aspect of the existence of science was carried out by a number of directions, the most famous of which can be considered positivism and neo-Kantianism. Consideration of this aspect of the existence of science still remains dominant in the philosophy of science. If in modern foreign philosophy of science this area of research is called epistemology (from the Greek episteme - scientific knowledge), then in domestic philosophy it is most often called logic and methodology of science. The range of problems associated with epistemology is quite wide. These include the problem of scientific criteria, reliability and objectivity scientific knowledge, as well as the basis for distinguishing scientific knowledge into fundamental and applied, the specifics of the empirical and theoretical levels of scientific research and their methods (such as experiment or mathematical modeling), features of the organization of scientific knowledge in facts, hypotheses, theories and much more.

2. Science is a special social phenomenon. This aspect of the existence of science has several manifestations. First of all, in the conditions of modern civilization, science is a type of social activity that has become a profession for a large number of people. Due to social needs and the need to organize the activities of those who are in one way or another connected with science, a multi-level and multifunctional system of scientific organizations has emerged. This system is called the social institution of science. In every cultural region and even in every single country social institution science has its own specifics, depending on the traditions and level of development of the country. So, for example, in modern Russia, science is institutionalized in such forms as university and academic science, research institutes, etc. factory science. The social aspect of the existence of science is also manifested in the fact that science plays an important role in life modern society, therefore it is quite legitimate to talk about the social functions of science, for example. about the influence of science on the development of technology: it is so significant that the very process of their mutual influence is called the scientific and technological revolution (or scientific and technological progress).

And finally, the social existence of science is expressed in the fact that the very content of scientific knowledge shows dependence on social relations and processes, i.e.

from what is happening in society. Science as a social phenomenon became the subject of study of the sociology of science, which arose in the 30s. XX century. Its prominent representatives are R. Merton (“Science, technology and civilization in England in the 17th century”), K. Manheim, J. Bernal (“Science in the history of society”, “ Social features science"). In its fundamental questions, the sociology of science merges with the philosophy of science, since without clarifying the social manifestations of science outlined above, it is impossible to understand its very essence. At the same time, the sociology of science includes a large array of applied research that describes the specific social parameters of its existence - in this part, the sociology of science goes beyond the philosophy of science. In addition to the sociology of science, we must also mention the sociology of knowledge, which studies the social conditioning of scientific knowledge, that is, one of the social manifestations of science. As an example, we can cite the works of M. Scheler “The Sociology of Knowledge” and M. Malkay “Science and the Sociology of Knowledge”.

3. Science is not only a special type of knowledge and a social phenomenon, it is also a unique cultural phenomenon. And this is the third aspect of the existence of science. The recognition of science as a cultural phenomenon in the philosophy of science occurs much later than the two aspects mentioned above. The reason for this is that the modern type of science (formed in modern times), in its desire to achieve the objectivity of knowledge, has abstracted as much as possible from everything that is not actually related to the object of study itself. In culture and in everything that is created by it, the human and subjective-personal is presented too clearly and obviously. And science, in fact, is the only means that can rise above the subjective and related human manifestations, and therefore over culture. In the philosophy of science, science was studied as a kind of extracultural (or supracultural) education. Science was viewed as a self-sufficient education and it was argued that in comparison, for example, with art, religion, morality, it is not influenced by cultural factors. This position is characteristic of positivism and, of course, is a certain extreme. A moderate approach on this issue is expressed in recognizing, but only the external connections of science and scientific ideas with religious, artistic, legal and other views. In particular, V.I. Vernadsky insisted on such a relationship between science and culture. And only in the 80s. of the last century, in the philosophy of science, an approach began to assert itself more and more actively, trying to give science the same cultural status as all other forms of culture (conventionally, such an approach could be called the culturology of science). The main argument of its supporters (among foreign researchers one can include I. Elkana, among domestic ones - G. Gachev, K. Svasyan) is the recognition of the cultural and historical conditionality of the very nature of science. They consider it legitimate and correct to talk about cultural and historical types of science, including European, Arab, Russian, etc. At the same time, it must be admitted that such an interpretation of science was developed quite thoroughly not in the philosophy of science itself, but in general philosophical reasonings of such thinkers as N. Ya. Danilevsky or O. Spengler (in time this refers to the mid-19th and first decades of the 20th century).

Having highlighted three aspects of the existence of science and indicated how they are developed in the philosophy of science, we must still keep in mind that separating these features of science from each other is a kind of abstraction. Science as a special type of cognitive activity, as a social phenomenon and as a cultural phenomenon is an integral unity. And this must be kept in mind modern philosophy science.

N. V. Bryanik

Scorpion